ECE Prof. Rick Johnson has signal processors and art historians talking about painting authenticationBy Robert EmroGrowing

up in northwestern Georgia, C. Richard Johnson Jr. never visited an art

museum, heard a classical music concert, or attended serious theater. A

second grader when the Soviets launched Sputnik I and the ensuing space

race, Johnson was channeled into engineering when he exhibited an early

aptitude for math and science. Not until he was a student at Georgia

Tech did he get his first taste of fine art.

He was in Germany with a study-abroad program. His travels took

|

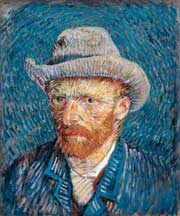

Self-Portrait in a Gray Felt Hat: Three Quarters to the Left, September 1887–October 1887. Courtesy The Van Gogh Museum.

-Van Gogh Museum

|

him to the Gemäldegalerie (Picture Gallery) in Berlin. This collection

of old masters was split by the wall when Johnson visited in the early

1970s. Even so, the West German side still held an impressive

collection, including The Man With the Golden Helmet, one of

Rembrandt’s most famous paintings. Seeing it for the first time was a

revelation. “I spent several hours in the Rembrandt rooms,” says

Johnson. “I didn’t know why. I just had some kind of response to it.”

From

a working-class family, Johnson didn’t even entertain the idea that he

could somehow make a career of art. “It never even crossed my mind at

that point,” he says. “That just wasn’t done where I come from.”

But

he couldn’t stay away. As an electrical engineering grad student at

Stanford, Johnson took a course on Rembrandt knowing that if he bombed,

the F would not appear in his record. Far from flunking, he was one of

the star pupils. During one test, he was the only person to realize

that a slide of a Frans Hals painting had been loaded backwards. He

could tell because Hals always painted the light falling from the left.

One class led to another and by the time Johnson graduated in 1977 he

had pioneered Stanford’s first Ph.D. minor in art history. The topic of

his final report, appropriately enough, was Vermeer’s use of the camera

obscura. Careful measurement of the angles in his paintings and

reconstructions of the rooms he painted them in have led some to argue

that Vermeer used this rudimentary optical device in creating his

almost photographic paintings.

“It was a survival technique to

get myself through engineering, to some extent,” says Johnson. “Art

history is something I found a passion for that I see in my students

for technical things that I sometimes don’t have.”

Johnson

received an appointment as an assistant professor at Virginia Tech, but

he was still drawn to art history and after a couple of years he put

together a book proposal on Rembrandt’s self-portraits. He knew he was

at a major fork in the road of his life, and he was willing to take a

different path, but it turned out Kenneth Clark had just written an

about-to-be published chapter on the same topic. His proposed

collaborator’s publisher rejected the proposal.

|

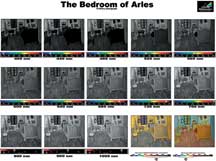

Lumiere Technology of Paris used its multi-spectral digital camera to capture images of van Gogh’s The Bedroom.

-Lumiere Technology

|

So

Johnson took a position at Cornell instead, joining the faculty as an

associate professor in 1981. He continued a successful academic

engineering career in the School of Electrical and Computer

Engineering, periodically reinventing himself. First he worked on the

theory behind adaptive feedback systems, used to kill the echo you can

sometimes hear while talking on the telephone, then he created and

analyzed blind equalization algorithms, used in receiving hi-def TV.

But he never lost his love of art history, so in 2005, when he was

ready to change his research focus once again, he began wondering how

his expertise in signal processing could get him a backstage museum

pass.

“When I decided to change, I looked for an area where I

would have some special talents,” he says. “I asked myself, ‘How can I

leverage something I know into getting behind the scenes?’”

Johnson

knew that art historians and curators used a variety of technologies to

study paintings, including X-radiography, infra-red photography, and UV

fluorescence. While on a Fulbright in Paris, Johnson arranged a lunch

meeting with Louis van Tilborgh, a curator at the Van Gogh Museum in

Amsterdam. He offered his services as a translator helping the art

history experts at the museum communicate with the technical types

doing the image processing. Tilborgh was intrigued and asked Johnson to

make a more formal presentation to museum management. While preparing,

Johnson discovered that these tools helped de-attribute the very

painting that awakened his passion for art in the first place. In 1985,

the Rembrandt Research Project determined The Man with the Golden

Helmet was not painted by Rembrandt but by an unnamed apprentice.

The

museum liked the idea of having an expert in signal processing to help

connect them with the computer-based technology used in painting

authentication and gave Johnson a five-year appointment as an adjunct

research fellow. “I’m a Ph.D. student again, working for the head of

conservation at the Van Gogh Museum, doing with her what she does and

finding out what we can give to a computer to do—which is mostly signal

processing,” he says. “Whether the data comes from a CAT scan or a

satellite or a painting, it becomes an array of numbers to which the

kit of signal processing tools can be applied.”

|

The Bedroom in 13 spectra, from ultra-violet to infrared, plus false color infrared and visible light.

-Lumiere Technology

|

“It’s quite a luxury for me to have a student that’s so efficient and

hardly needs any supervision. He’s so enthusiastic,” says Ella

Hendriks, Johnson’s new adviser. “He’s willing to spend time for things

that are hugely useful.”

While some in the art world balk at the

idea that a computer can perform the duties of a human art expert, the

Van Gogh Museum has embraced this new technology. “It’s not replacing

the judgment of the art historian, it’s simply an added tool that will

assist the art historian in making his judgment,” says Hendriks. “It’s

very important to make a good tool and the best way to do that is to

collaborate with the tool maker. If you’re involved at the beginning

you’re going to get the best tool.”

One thing Johnson has done

in his new role is connect the museum with a company in Paris—Lumiere

Technology—that has designed a multi-spectral camera for digitizing

works of art. The company used it to reveal the true colors of the Mona

Lisa in 2004. He helped convince Lumiere and the Van Gogh Museum to

take images of The Bedroom and The Potato Eaters in October. If all

goes well, the company will do the rest of the museum’s collection,

amassing a huge database for engineers and art historians to work with.

“It’s just been a dream to me because all the doors seemed to open up

for the asking,” says Johnson.

In a year or so, Johnson

envisions teaching a new course at Cornell examining how others have

approached using signal processing to authenticate art so students can

infer a general approach to the problem. He hopes his interaction with

the museum will eventually result in a textbook that combines art

history with technical material. “I’m not an engineering professor just

because I want to tinker with cool things,” he says. “I’m an academic

because I want to teach cool things.”

But first Johnson wants to

bring together the scattered groups working at this intersection of

engineering and fine art. “This is a field that doesn’t really exist

yet,” he says. “There are some people out there doing things, but not

as a cohesive field.”

|

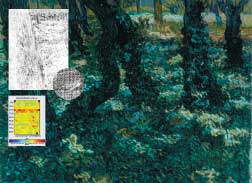

Once considered a Van Gogh, Still Life with Bottle of Wine, Two Glasses, and Plate with Bread and Cheese is now thought to be by an unknown friend of Vincent’s brother Theo.

-Van Gogh Museum

|

Dan

Rockmore, a professor of math and computer science at Dartmouth, has

been working with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to

authenticate Rembrandts. Professors Jia Lee and James Wang at Penn

State have identified the creators of Chinese ink paintings from the

15th to 20th centuries. And researchers led by Eric Postma at the

University of Maastricht in the Netherlands have developed a program

dubbed “Authentic” that can distinguish between the works of Van Gogh,

Cézanne, and Gaugin. Although they all use a variation of a technique

called stylometry, first developed to identify literary authors, they

had never met as a group to share ideas.

|

Working

with the gray scale values of each pixel in a digital image of the

painting, signal processors at the workshop were able to use wavelet

processing to corroborate the connoisseur’s determination.

-Van Gogh Museum

|

The

field is set to flourish. Research on how to best collect and organize

data from paintings is mature and recent technological advances have

enabled museums to amass huge databases of images. “The time is

certainly right in that people have been thinking about images

computationally for a long time. It certainly makes sense as a science

problem to compare images and see if you can find some commonality,”

says Rockmore. “The problem’s a totally natural one. Whether it has a

nice solution is one that everyone is working on. There are a lot of

aspects there and you only discover them when you drill down and treat

it as a science.”

Beyond determining if a painting is really by

a master, or just a clever forgery, forensic signal processing can help

art historians determine the sequence of an artist’s work, or

deconstruct a painter’s process by identifying which strokes went on

first. “There’s a lot of things I think [curators] can think of that

would be impossible, but there’s a lot of things we should be able to

do,” says Johnson. “Any time the art historian looks at the image for

the information they need, we should be able to help.”

To get

signal processors and art curators together, Johnson organized the

First International Workshop on Image Processing for Artist

Identification, held at the Van Gogh Museum May 14. Johnson convinced

the Van Gogh Museum and the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo,

Netherlands, to make digitized images of 101 of their paintings

available for analysis. Most are confirmed Van Goghs, but a few are now

attributed to others. This irresistible “goldmine” of data got several

groups of academic signal processors on board. To get them talking with

the attendees from museums across Europe, the daylong program

introduced curators to the capabilities of signal processing and

engineers to the techniques of connoisseurship, the traditional method

of authenticating paintings. Johnson’s unique background helped him get

the conversation rolling. “He knows both sides of the story, which is

needed,” says Hendriks. “He knows the words we use to talk about

things.”

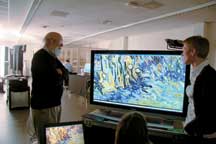

|

ECE

Prof. Rick Johnson and Van Gogh Museum Head of Conservation Ella

Hendriks observe a false color infrared digital image of Van Gogh’s Tree Trunks in the Grass captured by Lumiere Technology’s multi-spectral camera.

-Lumiere Technology

|

Six

months before the workshop, three teams of computer scientists,

mathematicians, electrical engineers, and statisticians from Penn

State, Princeton, and Maastricht universities set about to see if

mathematical analysis could find similarities in Van Gogh’s works not

present in the other paintings. They also checked the authentic

paintings against a 102nd, a modern copy of a Van Gogh commissioned by

WGBH’s Nova Science Now. The program taped the researchers at the

workshop and is scheduled to air on PBS nationally beginning next June.

All

three teams were successful to some degree at distinguishing real Van

Goghs from the copies. The Princeton team found a higher concentration

of high spatial frequency content, corresponding to an increased number

of small touches in the copies. This jibes with the commonly noted

tendency of copyists to use several small brush strokes to duplicate an

image that the original artist may have done in one stroke.

Even

more importantly, workshop participants expressed a desire for further

interaction. A repeat workshop was held Nov. 9 at the Museum of Modern

Art in New York City. Already, art historians and engineers around the

world are planning new projects based on the resulting

cross-fertilization. “The idea is to amplify this whole thing,” says

Johnson. “I’m sure there are signal processing research problems in

this area that people don’t yet know exist, and you can trip over them

a bunch of times without noticing them.”

A next step to building

a cohesive field, says Johnson, is to present problems to beginning

engineers so they can start thinking of creative new approaches to

solving them, just as in any other field of engineering. So Johnson has

been recruiting undergrads and M.Eng. students to work on an automated

thread-count project.

Yeounoh Chung got involved because it

was a little different from other projects he has worked on. “It seemed

like a really interesting project because it has to do with art,” says

the senior. “As an ECE student, all I’ve been doing is making something

that people don’t usually see, but this is more directly related to

something people can see and appreciate, so I thought it could be

something I could enjoy doing.”

|

Using

high-resolution digital images of x-rays, the automated thread count

method under development by Johnson and a team of students reveals a

strip (in red) of more tightly woven canvas in a corner of Van Gogh’s

Undergrowth. Such patterns can help art historians better sequence an

artist’s work or art curators restore paintings that have been cut into

pieces.

-Van Gogh Museum/Rick Johnson

|

Knowing

how many threads are in a canvas can reveal a lot to an art historian.

Thread counts of the canvases used by Van Gogh and Gauguin during their

time together at the Yellow House in Arles, France, in late 1888 helped

art historians to construct a timeline for the paintings during this

important period. Traditionally, thread counts are estimated using an

average of the number of threads hand-counted in five different

2-square-centimeter sections. It’s a tedious, time-consuming process

and museums would much rather allocate staff time to other work. A

computer could do it a lot faster, says Johnson, and by looking at more

samples, more thoroughly. Unlike typical hand counts, a computer count

is readily repeatable because it can keep an exact record of where it

has counted.

Technology alone won’t provide all the answers,

however. Without knowing that Van Gogh sometimes painted on canvas from

a limited number of bolts, thread counts would not have revealed much.

“It depends on the artist’s practice,” says Johnson. “So it’s a mixture

of knowing what they did and relating the physical evidence to that.”

The

project illustrates some of the differences in mind-set among

engineers, curators, and conservators. When Johnson first started

working on an automated thread-count program, he asked to see the

reference book that explains how art historians do such procedures and

was told there was no such book. Variations of the process are passed

verbally from expert to student. “But this can be broken down into an

ordered series of steps. We engineers see this because we’re taught to

do this in everything we do,” says Johnson. “Once we know the steps, we

can see where we can help. So, even in this unusual application, we’re

going to act like regular engineers and come into somebody else’s

application and use our skills to make their life better.”